Cellini's

statuary group "Perseus and Medusa" -- beautiful, in a sense, but the

kind of beauty that kills. As always, there are reasons for everything

and untangling this story may lead us to surprising discoveries. So, a piece by Paul Jorion on the debate that took place in Valladolid about

the destiny of the Native Americans in the Spanish empire made me aware

of why Western Art made an abrupt transition from Christian-inspired

Medieval subjects, to Pagan inspired Renaissance ones. Everything has an

explanation, indeed.

A couple of weeks days ago, I was taking a friend to visit Piazza Signoria, in Florence, showing him the many statuary pieces lining the square. All wonderful pieces, in many ways, but also disquieting for their depiction of murder and death. Today, nobody could get away with a piece of art where a sword-armed man beheads a naked woman. And yet this is exactly what one of the main pieces in the square shows to us: Perseus and Medusa in an unbelievably cruel, and at the same time eerily beautiful, depiction.

As I was showing the statue to my friend, I said, "you see, there is a sort of invisible wall that cuts the square in two. On one side there are older, Medieval pieces, inspired by Christian myths; David and Judith. On the other side, newer, Renaissance pieces inspired by classical myths from the Pagan age: Hercules and Perseus."

Then, I was asking myself, but why exactly that happened? What led people to switch their focus of interest from Christian myths to Pagan ones? I felt in need for an explanation, but I just I didn't have one at that moment.

I think it was two days later that a name flashed in my mind: Sepulveda! Juan

Gines de Sepulveda, one of the two discussants who debated in 1550-51 in Valladolid on the

status of the Native Americans in the newly conquered Spanish Empire in

Southern America and Mexico. I had just read, maybe a few days

before, the article by Paul Jorion about that

ancient dispute. Note that Cellini's "Perseus" had been made unveiled

in Florence in 1554, just a few years later.

Here is what Jorion writes about Sepulveda's position that favored the forced conversion of the Native Americans: "an Aristotelian philosopher who found in the texts of his mentor, not a justification for slavery, absent in fact from the texts of the Stagirite, but the description and the explanation of the slave society of ancient Greece, represented as a functional set of institutions: a legitimate model of human society". And here is the key of the whole story.

It all had started in 1492, with Columbus' voyage. Almost immediately afterward, it was clear that the Americas where an incredible business opportunity for Europeans. And also that the Native Americans couldn't oppose the European armies. There was only one thing that stood as a barrier against their complete enslavement or extermination: the stubborn opposition by the Catholic Church that insisted in considering the Natives as human beings with their own rights.

So, the Catholic Church was an obstacle to economic expansion and, then as now, there is little that can stop economic expansion. Sepulveda's position was simply recognizing this fact. The ancient world, that of the Romans and the Greeks, was not less civilized than the Europe of the 16th century, and they didn't shun slavery, especially for those whom they regarded as "barbarians." So, why should Europe not enforce it on people who were manifestly inferior in terms of civilization? Sepulveda was officially defeated at Valladolid by the arguments of Bartolomé de Las Casas, who favored a more humane approach toward Native Americans. But, in later years it was clear that Sepulveda had been the true winner. His views appeared not just in the way the Native Americans were treated, but also in the European art of that period.

Below,

you'll find the post by Paul Jorion that tells

the true story. From our viewpoint, neither of the two discussants in

Valladolid had a position that we would accept, but at least the debate

had the interests of the Native Americans, considered as human beings,

as the focus. And the end result was an attempt to help the natives to

maintain their rights of human beings. But, as you may have expected,

the law was often ignored. The result was a series of disasters that

Bartolomé the Las Casas described in his "A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies"

(1522). The book was not intended to be an accusation on religion, but

it was turned into it by anti-Spanish propaganda created by those who

were actually exterminating the Natives, the British and North European

colonists. The Catholic Church received such a blow from this campaign

that it never completely recovered from it. And we still believe this ancient propaganda, nearly half a millennium later!

And now you understand why Cellini sculpted Perseus the way he did.

The "quarrel" or "controversy" of Valladolid (1550-1551)

This text will find its place in the panorama of anthropology that I am writing at the moment. As this is a subject that I am new to and where I cannot avail myself of any expertise, please be so kind as to point out to me any factual errors I make. Thank you in advance !

In 1550 and 1551 a debate took place in the city of Valladolid in Spain, which would go down in history as the “quarrel” or “controversy,” bearing the name of this city in the province of Castile and Leon.

What was it about? It dealt with the Christian European civilization behaving like an

unscrupulous invader on a continent of which it knew nothing, within

populations of which it was until then unaware of the very existence,

which it then discovered in real time as it grew. advance in the

territory of the New World, and the devastation that accompanied this

advance.

What all this meant as to how the

victors would now treat the vanquished would be the question posed in a

great debate that would cover a period of two years and where two

champions of Spanish thought at the time would face off. Great

intellectual and ethical problems had to be resolved in the scholastic

tradition of a disputatio, before the enlightened public

of what we would today call a commission, which would decide at the end

of the debate which of the two speakers was right. There were basically only church people there.

Two thinkers were be on stage, both solemnly defending opposing points of view. They clashed at the level of ideas by mobilizing all the art of dialectics: that intended to convince, an art developed specifically for the speeches held in ancient Greece on an agora. To defend one of the points of view, Juan Gines de Sepulveda (1490-1573) considered, in a word, that the inhabitants of the New World were cruel savages and that the question was essentially of saving them from themselves. And, to defend the opposing point of view, there was the Dominican Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474-1566) who affirmed that the Amerindians were, like the Europeans, human beings, whose differences should not be exaggerated, and that the question was about integrating them peacefully into a Christian society by conviction rather than by force.

The brutal conquest of Mexico took place from 1519 to 1521, it was no less bloody of Peru from 1528 to 1532. We are now in 1550, almost twenty years after this last date. The situation, from the point of view of the Spaniards, is that they have won: the huge empire of New Spain has been conquered by secular Spain. It is a victory, even if internal quarrels continue, on the one hand between the colonized, as at the time of the conquest, which their incessant dissensions had fostered, and on the other hand between the colonizers themselves, manifested by a litany of palace revolutions and assassinations of conquistadors between them, in Peru as in Mexico.

But the time has come for Charles V (1500-1558), “Emperor of the Romans”, to take a break. We must think about how to treat these conquered populations, decimated in equal parts by battles and massacres, and by the ravages of smallpox and measles, against which the local populations were helpless, having no immunity to these diseases hitherto absent from the continent. It is considered today that Mexico had some 25 million inhabitants on the eve of the first landing of the Spaniards in 1498. In 1568, the population was estimated at 3 million and it is believed that in 1620 there were only a million and a half Mexicans left.

The phase still to come would no longer be that of Mexico or Peru, whose conquest was completed and where colonization was then carried out well, but that of Paraguay, which would begin in 1585, thirty-five years later.

Charles V, was an enlightened sovereign, like his rival François 1 st. They were contemporaries: two thinking kings, not only just, but men who had questions about the history, knowing that they were major players. They shared a conception of the world enlightened by the same religion: Catholicism. The reign of Charles V will end a few years later: in 1555. It will then be his son Philip who will become sovereign of Spain and the Netherlands. Later, in 1580, he will also be King of Portugal. Charles V demands that any new conquest be interrupted as long as Las Casas and Sepulveda exchange their arguments on the question of the status to be recognized for the indigenous populations of the New World.

Charles V had not, however, remained indifferent to these questions even before: already in 1526, 24 years before the Valladolid controversy, he had issued a decree prohibiting the slavery of Amerindians throughout the territory, and in 1542, he had promulgated new laws which proclaimed the natural freedom of the Amerindians and obliged to release those who had been reduced to slavery: freedom of work, freedom of residence and free ownership of property, punishing, in principle, those who were violent and aggressive towards Native Americans.

Paul III was pope from 1534 to 1549. In 1537, thirteen years before the beginning of the Valladolid controversy, in the papal bull Sublimis Deus and in the letter Veritas Ipsa, he had officially condemned, on behalf of the Catholic Church, the slavery of the Native Americans. The statement was "universal," that is, it was applicable wherever the Christian world could still discover populations unknown to it on the surface of the globe: it was said in Sublimis Deus: " and of all peoples that may be later discovered by Christians ”. And in both documents, so in Veritas Ipsa too: "Indians and other peoples are true human beings."

When the quarrel began, Julius III had just succeeded Paul III: he was enthroned on February 22, 1550.

The general principle, for Charles V, was that of aligning with the Church policy. In the "quarrel" or "controversy" of Valladolid, one of the moments of solemn reflection of humanity on itself, it is not the Church, but the Kingdom of Spain, which summons religious authorities , experts, to try to answer the question "What can be done so that the conquests still to come in the New World are done with justice and in security of conscience?"

It is heartbreaking that the television film “La controverse de Valladolid” (1992), by Jean-Daniel Verhaeghe, with Jean-Pierre Marielle in the role of Las Casas and Jean-Louis Trintignant in that of Sepulveda, as well as the novel by Jean- Claude Carrière, from whom it was inspired, took such liberties with historical truth that it was affirmed that the central question in the quarrel was to determine whether the Amerindians had a soul. No: this question had been settled by the Church without public debate thirteen years earlier. Sublimis Deus affirms that their property and their freedom must be respected, and further specifies "even if they remain outside the faith of Jesus Christ", that is to say that the same attitude must be maintained even if they are rebellious to conversion. It is written in the Papal Bull Veritas Ipsa that Native Americans are to be “invited to the said faith of Christ by the preaching of the word of God and by the example of a virtuous life. »In 1537: thirteen years before the commission met.

The question of the soul of the Amerindians was of course raised in Valladolid, but in no way to try to resolve it: on this level, the issue was closed. In reality, it had been resolved in the real world by the Spanish invaders: it would have been possible to summon young men and women of mixed race in their twenties to Valladolid, including Martin, son of Ernan Cortés and Doña Marina, “La Malinche”: living proof that the human species had recognized itself as “one and indivisible” in the field and that the question of whether these people, whom their mother could accompany if necessary, dressed in Spanish fashion, and most often militants of Christianity in their actions and in their words. Whether or not they had a soul, would have been an entirely abstract and ridiculous question, the problem having been solved in the facts: in the interbreeding which took place, in this reality that men and women have recognized themselves sufficiently similar not only to mate and immediately procreate, but to sanctify their marriage, in a sumptuous way for the richest, according to the rites of the Church. Circumstances, it must be emphasized, the opposite of the rules that were followed in North America, while in the case of Protestant settlers in their almost all - except Quebec - from the end of the 16th century.

The meetings in Valladolid were eld twice over a month, in 1550 and then in 1551, but most of the texts available to us are not transcripts of the debates: they are correspondence between the parties involved: Juan Gines de Sepulveda, Bartolomé de Las Casas, and the members of the commission.

Las Casas had first been himself an encomendero, a slave settler: he led plantations where Native American slaves were originally found, plantations in which, reacting to the Church's commands to give back their freedom to the natives enslaved, he had replaced on his own authority the labor of Amerindian slaves that he ceased to exploit with other laborers: blacks imported from Africa. This will be a great regret in his life, he will talk about it later. Most of the encomenderos were not as attentive as Las Casas to instructions from the mother country or the Vatican. Already in 1511, in Santo Domingo, the Dominican Antonio de Montesinos, who exercised a decisive influence on Las Casas, refused the sacraments and threatened with excommunication those among them whom he considered unworthy. Here is his famous sermon:

"I am the voice of the One who cries in the desert of this island and that is why you must listen to me with attention. This voice is the freshest you have ever heard, the harshest and the most tough. This voice tells you that you are all in a state of mortal sin; in sin you live and die because of the cruelty and tyranny with which you overwhelm this innocent race.

Tell me, what right and what justice authorize you to keep the Indians in such dreadful servitude? In the name of what authority have you waged such hateful wars against those peoples who lived in their lands in a gentle and peaceful way, where a considerable number of them were destroyed by you and died in yet another way? never seen as it is so atrocious? How do you keep them oppressed and overwhelmed, without giving them food, without treating them in their illnesses which come from excessive work with which you overwhelm them and from which they die? To put it more accurately, you kill them to get a little more gold every day.

And what care do you take to instruct them in our religion so that they know God our creator, so that they are baptized, that they hear Mass, that they observe Sundays and other obligations?

Are they not men? Are they not human beings? Must you not love them as yourselves?

Be certain that by doing so, you cannot save yourself any more than the Moors and Turks who refuse faith in Jesus Christ. "

Las Casas' reflection led him to give up this role of planter and he took a step back for several years. Charles V then offered him access to vast lands in Venezuela on which he could implement the policy he now advocated towards the Amerindians: no longer the use of force, but the power of conviction and conversion by example. Las Casas was a Thomist. Following the line drawn by Thomas Aquinas, he read in human society a given of nature. It is not a question of a cultural heritage, that is to say of the fruit of the deliberations of men, but of a gift from God, so that all societies are of equal dignity, and a society of Pagans is no less legitimate than a society of Christians and it is wrong to attempt to convert its members by force. The propagation of the faith must be done there in an evangelical way, namely by virtue of example.

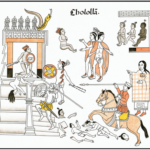

Facing Las Casas, Sepulveda stood: an Aristotelian philosopher who found in the texts of his mentor, not a justification for slavery, absent in fact from the texts of the Stagirite, but the description and the explanation of the slave society of ancient Greece, represented as a functional set of institutions: a legitimate model of human society. Sepulveda considered slavery, obedience to orders given, to be the status that suits a people who, left to themselves, commit, as we can observe, nameless abominations. Sepulveda finds argument in the atrocities committed, in particular the uninterrupted practice of human sacrifice, for which the populations brutally enslaved by the dominant society of the moment, constitute an inexhaustible source of victims, but also their anthropophagy, as well as their practice of incest. in the European sense of the term: fraternal and sororal incest within the framework of princely families in Mexico, "incestuous promiscuity" if you will, in the pooling of women among brothers, a difficulty that the Jesuits later encountered in the case of the Guaranis of Paraguay, which they will resolve by banning the “longhouse”, the collective dwelling of siblings.

Las Casas responded to Sepulveda by stressing that Spanish civilization is no less brutal: "We do not find in the customs of the Indians of greater cruelty than that which we ourselves had in the civilizations of the old world." Very diplomatically, he draws his examples from the past and says "formerly:" "In the past, we manifested a similar cruelty", highlighting for example the gladiatorial fights of ancient Rome. He also drew an argument from the monumental architecture of the Aztecs as proof of their civilization.

If the two points of view differed, and even if their positions were considered diametrically opposed, the two parties agreed on the fact that the invaders not only have rights to exercise over the Amerindians but also duties towards them, and in particular, in the context of the time and the question to be answered. There is no dispute between them as to the duty to convert: this is the dimension strictly speaking "Catholic" from the very framework of the debate. Their difference lies in their respective recommendations of the methods to be used: peaceful colonization and exemplary life for Las Casas and, for Sepulveda, institutional colonization based on coercion, given the brutal features of the very culture of the pre-Colombian populations.

Let us remember that the context was extremely brutal texts on both sides. Las Casas, at the end of his life, will write a small book devoted only to the atrocities committed by the conquistadors, a small book that propaganda consistently used against Spain to advantage its rivals: the Netherlands, France and England, although this does not mean that these nations will not also be guilty of the same crimes in the territories that they will annex in their business colonial. Mutual surveillance therefore of European nations vis-à-vis possible abuses committed by others, from a diplomatic perspective of foreign policy.

The controversy officially ended in 1551 when Charles V, on the recommendations of the commission, formalized the position defended by Las Casas. It will therefore be by invoking the Gospels and by example that conversion will have to continue and not at the point of the sword.

A victory which, however, will not immediately have enormous consequences on the ground, any more than the papal bulls had had before it. The encomenderos will only weakly respect the injunctions coming from the mother country. Wars between Amerindian tribes will continue despite the presence of missionaries and a small military contingent. The Bandeirantes of Sao Paulo will organize raids, supplying the encomenderos with prisoners, who will be on the plantations, as many de facto slaves. Etc.

A year after the controversy was over, in 1552, Las Casas undertook to write his Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias , the very brief account of the destruction of the Indies, which will therefore be his testimony on the destructions and the atrocitie, of the colonization of New Spain by the Spaniards.

When, from the end of the same century, missions are founded in Paraguay, called "Reductions", it will be in the exact line of the proposals of Las Casas.

It will be essentially Las Casas who will obtain, thanks to his vibrant plea in favor of the local populations, that the question of slavery would be closed once and for all in Central and South America: there will be no indigenous slaves, Amerindians will be considered as full citizens and, as an unexpected consequence, since the Church has not pronounced on the question of knowing whether Africans could be enslaved or not, the Spanish and Portuguese authorities will consider that the decision in favor of the position of Las Casas opens suddenly the possibility of a systematic exploitation of the African populations to draw from them the stock of slaves required by the plantations of the New World. It is Las Casas who will be in a way responsible for an acceleration of the slavery of Africans insofar as the authorities, both civil and ecclesiastical, by discouraging the enslavement of the Amerindians, will indirectly encourage the planters to turn, as a replacement, towards the slave trade in African blacks, a situation in which Las Casas found himself at the time when he was encomendero. In his correspondence, at the end of his life, he bitterly regretted having been indirectly the cause of an aggravated enslavement of Africans.

The sincere concern of Bartolomé de Las Casas to spare the

Amerindians, will have preserved them from the even more tragic fate of

their brothers and sisters of North America within the framework of an

essentially English colonization at the start, made of spoliation and

genocide, without any interbreeding.