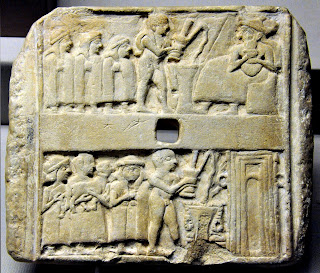

Temple

worship in Ur, from Sumerian times. Note in the lower panel people are

bringing all sort of goods to the temple represented as the abstract

structure on the right.

House

founded by An, praised by Enlil, given an oracle by mother Nintud! A

house, at its upper end a mountain, at its lower end a spring!

A house, at its upper end threefold indeed. Whose well-founded

storehouse is established as a household, whose terrace is supported by

lahama deities; whose princely great wall, the shrine of Urim! (the Kesh temple hymn, ca. 2600 BCE)

Not long ago, I found myself involved in a debate on Gaian religion convened by

Erik Assadourian.

For me, it was a little strange. For the people of my generation,

religion is supposed to be a relic of the past, opium of the people, a

mishmash of superstitions, something for old women mumbling ejaculatory

prayers, things like that. But, here, a group of people who weren't

religious in the traditional sense of the word, and who included at

least two professional researchers in physics, were seriously discussing

about how to best worship the Goddess of Earth, the mighty, the

powerful, the divine, the (sometimes) benevolent

Gaia, She

who keeps the Earth alive.

It was not just unsettling, it was a deep rethinking of many things I

had been thinking. I had been building models of how Gaia could function

in terms of the physics and the biology we know. But here, no, it was

not Gaia the

holobiont, not Gaia the superorganism, not Gaia the homeostatic system.

It was Gaia the Goddess.

And here I am, trying to explain to myself why I found this matter worth

discussing. And trying to explain it to you, readers. After all, this

is being written in a blog titled "

Chimeras"

-- and the ancient Chimera was a myth about a creature that, once, must

have been a sky goddess. And I have been keeping this blog for several

years, see? There is something in religion that remains interesting even

for us, moderns. But, then, what is it, exactly?

I mulled over the question for a while and I came to the conclusion

that, yes, Erik Assadourian and the others are onto something: it may be

time for religion to return in some form. And if religion returns, it may well be in the form of some kind of cult of the Goddess Gaia. But let me try to explain

What is this thing called "religion," anyway?

Just as many other things in history that go in cycles, religion does

that too. It is because religion serves a purpose, otherwise it wouldn't

have existed and been so common in the past. So what is religion? It is

a long story but let me start from the beginning -- the very beginning,

when, as the Sumerians used to say "Bread was baked for the first time

in the ovens".

A constant of all ancient religions is

that they tell us that whatever humans learned to do -- from fishing to

having kings -- it was taught them by some God who took the trouble to

land down from heaven (or from wherever Gods come from) just for that

purpose. Think of when the Sumerian Sea-God called

Aun (also

Oannes in later times) emerged out of the

Abzu (that today we call the

abyss)

to teach people all the arts of civilization. It was in those ancient

times that the Gods taught humans the arts and the skills that the

ancient

Sumerians called "me," a bewildering variety of

concepts, from "music" to "rejoicing of the heart." Or, in a more recent lore, how Prometheus

defied

the gods by stealing fire and gave it to humankind. This story has a

twist of trickery, but it is the same concept: human civilization is a

gift from the gods.

Now, surely our ancestors were not so naive that they believed in these

silly legends, right? Did people really need a Fish-God to emerge out of

the Persian Gulf to teach them how to make fish hooks and fishnets?

But, as usual, what looks absurd hides the meaning of complex questions.

The people who described how the

me came from the Gods were not naive, not at all. They had understood the essence of civilization, which is

sharing.

Nothing can be done without sharing something with others, not even

rejoicing in your heart. Think of "music," one of the Sumerian

me:

can you play music by yourself and alone? Makes no sense, of course.

Music is a skill that needs to be learned. You need teachers, you need

people who can make instruments, you need a public to listen to you and

appreciate your music. And the same is for fishing, one of the skills

that

Aun taught to humans. Of course, you

could fish by

yourself and for your family only. Sure, and, in this way, you ensure

that you all will die of starvation as soon as you hit a bad period of

low catches. Fishing provides abundant food in good times, but fish

spoils easily and

those who live by fishing can survive only if they share their catch

with those who live by cultivating grains. You can't live of fish alone,

it is something that I and my colleague Ilaria Perissi describe in our

book, "

The Empty Sea." Those who tried, such as the Vikings of Greenland during the Middle Ages, were mercilessly wiped out of history.

Sharing

is the essence of civilization, but it is not trivial: who shares what

with whom? How do you ensure that everyone gets a fair share? How do you

take care of tricksters, thieves, and parasites? It is a fascinating

story that goes back to the very beginning of civilization, those times

that the Sumerians were fond to tell with the beautiful image of "when

bread was baked for the first time in the ovens," This is where

religion came in, with temples, priest, Gods, and all the related stuff.

Let's make a practical example: suppose

you are on an errand, it is a hot day, and you want a mug of beer.

Today, you go to a pub, pay a few dollars for your pint, you drink it,

and that's it. Now, move yourself to Sumerian times. The Sumerians had

plenty of beer, even a specific goddess related to it, called Ninkasi

(which means, as you may guess, "the lady of the beer"). But there were

no pubs selling beer for the simple reason that you couldn't pay for

it. Money hadn't been

invented, yet. Could you barter for it? With what? What could you carry

around that would be worth just one beer? No, there was a much better

solution: the temple of the local God or Goddess.

We have beautiful descriptions of the Sumerian temples in the works of

the priestess Enheduanna, among other things the first named author in

history. From her and from other sources, we can understand how in

Sumerian times, and for millennia afterward, temples were large

storehouses of goods. They were markets, schools, libraries,

manufacturing center, and offered all sorts of services, including that

of the hierodules (

karkid in Sumerian), girls who were not

especially holy, but who would engage in a very ancient profession that

didn't always have the bad reputation it has today. If you were so

inclined, you could also meet male prostitutes in the temple, probably

called "

kurgarra" in Sumerian. That's one task in whicb temples

have been engaging for a long time, even though that looks a little

weird to us. Incidentally, the Church of England

still managed prostitution in Medieval times

So,

you go to the temple and you make an offer to the local God or Goddess.

We may assume that this offer would be proportional to both your needs

and your means. It could be a goat that we know it was roughly

proportional to

the services of a high-rank hierodule.

But, if all you wanted was a beer, then you could have limited your

offer to something less valuable: depending on your job you could have

offered fish, wheat, wool, metal, or whatever. Then, the God would be

pleased and as a reward the alewives of the temple would give you all

the beer you could drink. Seen as a restaurant, the temple worked on the

basis of what we call today an "all you can eat" menu (or "the

bottomless cup of coffee," as many refills as you want).

Note how the process of offering something to God was called sacrifice.

The term comes from

"sacred" which means "separated." The sacrifice is about separation. You

separate from something that you perceived as yours which then becomes

an offer to the God or to the community -- most often the same thing.

The offerings to the temple could be something very simple: as you see

in the images we have from Sumerian times, it didn't always involve the

formal procedure of killing a live animal. People were just bringing the

goods they had to the temple. When animals were sacrificed to God(s) in

the sense that they were ritually killed, they were normally eaten

afterward. Only in rare cases (probably not in Sumeria) the sacrificed

entity was burnt to ashes. It was the "burnt sacrifice called korban olah

in the Jewish tradition. In that case, the sacrifice was shared with

God alone -- but it was more of an exception than the rule.

In

any case, God was the supreme arbiter who insured that your sacrifice

was

appreciated -- actually not all sacrifices were appreciated. Some people

might try to trick by offering low quality goods, but God is not easy

to fool. In some cases, he didn't appreciate someone's sacrifices at

all: do you remember the story of Cain and Abel? God rejected Cain's

sacrifice, although we are not told exactly why. In any case, the

sacrifice was a way to attribute a certain "price" to the sacrificed

goods.

This method of commerce is not very

different than the one we use today, it is just not so exactly

quantified as when we use money to attach a value to everything. The

ancient method works more closely to the principle that the Marxists had

unsuccessfully tried to implement "from each according to his ability,

to each according to his needs." But don't think that the ancient

Sumerian were communists, it is just that the lack of method of

quantification of the commercial transaction generated a certain leeway

that could allow to the needy access to the surplus available, when it

was available. This idea is still embedded in modern religions, think of

how the holy Quran commands the believers to share the water of their

wells with the needy, once they have satisfied their needs and those of

their animals. Or the importance that the Christian tradition gives to

gleaning as a redistribution of the products of the fields. Do you

remember the story of Ruth the Moabite in the Bible? That important,

indeed.

But there is more. In the case of a burnt sacrifices, the value attributed to the goods was "infinite"

-- the goods consumed by the flames just couldn't be used again by

human beings. It is the concept of Taboo used in Pacific cultures

for something that cannot be touched, eaten, or used. We have no

equivalent thing in the "market," where we instead suppose that

everything has a price.

And then, there came money (the triumph of evil)

The world of the temples of the first 2-3 millennia of human

civilizations in the Near East was in some ways alien to ours, and in others

perfectly equivalent. But things keep changing and the temples were

soon to face a competition in a new method of attributing value to

goods: money. Coinage is a relatively modern invention, it goes back to

mid 1st millennium BCE. But in very ancient times, people did exchange

metals by weight -- mainly gold and silver. And these exchanges were

normally carried out in temples -- the local God(s) ensured honest

weighing. In more than one sense, in ancient times temples were banks and it is no coincidence that our modern banks look like temples. They are temples to a God called "money." By the way, you surely read in the Gospels how Jesus chased the money changers -- the trapezitai

-- out of the temple of Jerusalem. Everyone knows that story, but what

were the money changers doing in the temple? They were in the

traditional place where they were expected to be, where they had been

from when bread was baked in ovens for the first time.

So, religion and money evolved in parallel -- sometimes complementing

each other, sometimes in competition with each other. But, in the long

run, the temples seem to have been the losers in the competition. As

currency became more and more commonplace, people started thinking that

they didn't really need the cumbersome apparatus of religion, with its

temples, priests, and hierodules (the last ones were still appreciated,

but now were paid in cash). A coin is a coin is a coin, it is guaranteed by

the gold it is made of -- gold is gold is gold. And if you want a good

beer, you don't need to make an offer to some weird God or Goddess. Just

pay a few coppers for it, and that's done.

The

Roman state was among the first in history to be based nearly 100% on

money. With the Romans, temples and priests had mainly a decorative

role, let's say that they had to find a new market for their services.

Temples couldn't be anymore commercial centers, so they reinvented

themselves as lofty place for the celebration of the greatness of the

Roman empires. There remained also a diffuse kind of religion in the

countryside that had to do with fertility rites, curing sickness, and

occasional cursing on one's enemies. That was the "pagan" religion, with

the name "pagan" meaning, basically, "peasant."

Paganism

would acquire a bad fame in Christian times, but already in Roman times

peasant rites were seen with great suspicion. The Romans burned

witches, oh, yes, they loved to burn witches -- they burned many more

than would ever be burned in medieval times. And the victims were most

likely countryside enchanters and enchantresses. They were considered

dangerous because the real deity that the Romans worshiped was money. An

evil deity, perhaps, but it surely brought mighty power to the Romans,

but their doom as well, as it is traditional for evil deities. Roman

money was in the form of precious metals and when they ran out of gold

and silver from their mines, the state just couldn't exist anymore: it

vanished. No gold, no empire. It was as simple as that.

The disappearance of the Roman state saw a return of religion, this time in the form of Christianity. It is

a long story that

would need a lot of space to be written. Let's just say that the Middle

Ages in Europe saw the rise of monasteries to play a role similar to

that of temples in Sumerian times. Monasteries were storehouses,

manufacturing centers, schools, libraries, and more -- they even had something to do with hierodules. During certain

periods, Christian nuns

did seem to have played that role,

although this is a controversial point. Commercial exchanging and

sharing of goods again took a religious aspect, with the Catholic Church

in Western Europe playing the role of a bank by guaranteeing that, for

instance,

ancient relics were authentic.

In part, relics played the role that money had played during the Roman

Empire, although they couldn't be exchanged for other kinds of goods.

The miracle of the Middle Ages in Europe was that this arrangement

worked, and worked very well. That is, until someone started excavating

silver from mines in Eastern Europe and another imperial cycle started.

It is not over to this date, although it is clearly declining.

So,

where do we stand now? Religion has clearly abandoned the role it had

during medieval times and has re-invented itself as a support for the

national state, just as the pagan temples had done in Roman times. One of the

most tragic events of Western history is when in 1914, for some

mysterious reasons, young Europeans found themselves killing each other

by the millions while staying in humid trenches. On both sides of the trenches, Christian priests were

blessing the soldiers of "their" side, exhorting them to kill those of

the other side. How Christianity could reduce itself to such a low level

is one of the mysteries of the Universe, but there

are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our

philosophy. And it is here that we stand. Money rules the world and

that's it.

The Problem With Money

Our society is perhaps the most monetized of

history -- money pervades every aspect of life for everyone. The US is

perhaps the most monetized society ever: for Europeans it is a shock to

discover that many American families

pay their children

for doing household chores. For a European, it is like if your spouse

were asking you to pay for his/her sexual services. But different epochs have

different uses and surely it would be shocking for a Sumerian to see

that we can get a beer at the pub by just giving the alewives a curious

flat object, a "card," that they then give back to us. Surely that card

is a powerful amulet from a high-ranking God.

So,

everything may be well in the best of worlds, notoriously represented

by the Western version of liberal democracy. Powerful market forces,

operated by the God (or perhaps Goddess) called Money or, sometimes,

"the almighty dollar," ensure that exchanges are efficient, that scarce

resources are optimally allocated, and that everyone has a chance in the

search for maximizing his/her utility function.

Maybe.

But it may also be that something is rotten in the Great Columned

Temple of Washington D.C. What's rotten, exactly? Why can't this

wonderful deity we call "money" work the way we would it like to, now

that we even managed to decouple it from the precious metals it was made

of in ancient times?

Well, there is a problem. A big problem. A gigantic problem. It is simply that money is evil. This

is another complex story, but let's just say that the problem with evil

and good is that evil knows no limits, while good does. In other words,

evil is equivalent to chaos, good to order. It has something to do with

the definition of "obscenity." There is nothing wrong in human sex, but an excess of sex in some forms becomes

obscene. Money can become obscene for exactly this reason: too much of it

overwhelms everything else. Nothing is so expensive that it cannot be

bought; that's the result of the simple fact that you can attribute a

price to everything.

Instead, God is good

because She has limits: She is benevolent and merciful. You could see

that as a limitation and theologians might discuss why a being that's

all-powerful and all-encompassing cannot be also wicked and

cruel. But there cannot be any good without an order of things. And

order implies limits of some kind. God can do everything but He cannot

do evil. That's a no-no. God cannot be evil. Period.

And

here is why money is evil: it has no limits, it keeps accumulating. You

know that accumulated money is called "capital," and it seems that many

people realize that there is something wrong with that idea because

"capitalism" is supposed to be something bad. Which may be but, really, capital

is one of those polymorphic words that can describe many things, not all of them necessarily bad. In

itself, capital is simply the accumulation of resources for future use

-- and that has limits, of course. You can't accumulate more things than

the things you have. But once you give a monetary value to this

accumulated capital, things change. If money has no limits, capital

doesn't, either.

Call it capital or call

it money, it is shapeless, limitless, a blob that keeps growing and

never shrinks.

Especially nowadays that money has been decoupled from material goods

(at least in part, you might argue that money is linked to crude

oil). You could say that money is a disease: it affects everything.

Everything can be associated with a number, and that makes that thing

part of the entity we call market. If destroying that thing can raise

that number, somewhere, that thing will be destroyed. Think of a tree:

for a modern economist, it has no monetary value until it is felled and

the wood sold on the market. And that accumulates more money, somewhere.

Monetary capital actually destroys natural capital. You may have heard

of "Natural Capitalism" that's supposed to solve the problem by giving a price to trees even before they are felled. It could

be a good idea, but it is still based on money, so it may be the wrong

tool to use even though for a good purpose..

The

accumulation of money in the form of monetary capital has created

something enormously different than something that was once supposed to

help you get a good beer at a pub. Money is not evil just in a

metaphysical sense. Money is destroying everything. It is destroying the

very thing that makes humankind survive: the Earth's ecosystem. We call

it "overexploitation," but it means simply killing and destroying

everything as long as that can bring a monetary profit to someone.

Re-Sacralizing The Ecosystem (why some goods must have infinite prices)

There

have been several proposals on how to reform the monetary system, from

"local money" to "expiring money," and some have proposed to simply get

rid of it. None of these schemes has worked, so far, and getting rid of

money seems to be simply impossible in a society that's as complex as

ours: how do you pay the hierodules if money does not exist? But from what I have been discussing so far, we could avoid the

disaster that the evil deity calling money is bring to us simply by

putting a limit to it. It is, after all, what the Almighty did with the

devil: She didn't kill him, but confined him in a specific area that we

call "Hell" -- maybe there is a need for hell to exist, we don't know.

For sure, we don't want hell to grow and expand everywhere.

What

does it mean a limit to money? It means that some things must

be placed outside the monetary realm -- outside the market. If you want

to use a metaphor based on economics, some goods must be declared to

have an "infinite" monetary price -- nobody can buy them, not

billionaires, not even trillionaires or any even more obscene levels of

monetary accumulation. If you prefer, you may use the old Hawai'ian

word: Taboo. Or, simply, you decide that some things are sacred, holy, they are beloved by the Goddess and even thinking of touching them is evil.

Once

something is sacred, it cannot be destroyed in the name of profit. That

could mean setting aside some areas of the planet, declaring them not

open for human exploitation. Or setting limits to the exploitation, not

with the idea of maximizing the output of the system for human use, but

with the idea to optimize the biodiversity of the area. These ideas are

not farfetched. As an example, some areas of the sea have been declared

"whale sanctuaries" -- places where whales cannot be hunted. That's not

necessarily an all/zero choice. Some sanctuaries might allow human

presence and a moderate exploitation of the resources of the system. The

point is that as long as we monetize the exploitation, the we are back

to monetary capitalism and the resource will be destroyed.

Do

we need a religion to do that? Maybe there are other ways but, surely,

we know that it is a task that religion is especially suitable for.

Religion is a form of communication that uses rituals as speech.

Rituals are all about sacralization: they define what's sacred by means

of sacrifice. These concepts form the backbone of all religions,

everything is neatly arranged under to concept of "sacredness" -- what's

sacred is nobody's property. We know that it works. It has worked in

the past. It still works today. You may be a trillionaire, but you are

not allowed to do everything you want just because you can pay for it.

You can't buy the right of killing people, for instance. Nor to destroy

humankind's heritage. (So far, at least).

Then, do we need a new religion for that purpose? A Gaian religion?

Possibly

yes, taking into account that Gaia is not "God" in the theological

sense. Gaia is not all-powerful, she didn't create the world, she is

mortal. She is akin to the Demiurgoi, the Daimonoi, the Djinn,

and other similar figures that play a role in the Christian, Islamic

and Indian mythologies. The point is that you don't necessarily need the

intervention of the Almighty to sacralize something. Even just a lowly

priest can do that, and surely it is possible for one of Her Daimonoi, and Gaia is one.

Supposing

we could do something like that, then we would have the intellectual and

cultural tools needed to re-sacralize the Earth. Then, whatever is

declared sacred or taboo is spared by the destruction

wrecked by the money based process: forests, lands, seas, creatures

large and small. We could see this a as a

new alliance between humans and Gaia: All the Earth is sacred to

Gaia, and some parts of it are especially sacred and cannot be touched by money. And not just the Earth, the poor,

the weak, and the dispossessed among humans, they are just as sacred and

must be respected.

All that is not just a

question of "saving the

Earth" -- it is a homage to the power of the Holy Creation that belongs

to

the Almighty, and to the power of maintenance of the Holy Creation that

belongs to the Almighty's faithful servant, the holy Gaia, mistress of

the ecosystem. And humans, as the ancient Sumerians had already

understood, are left with the task of respecting, admiring and

appreciating what God has created. We do not worship Gaia, that would

silly, besides being blasphemous. But through her, we worship the higher

power of God.

Is it possible? If history tells us something is that money tends to beat

religion when conflict arises. Gaia is powerful, sure, but can she slay

the money dragon in single combat? Difficult, yes, but we should

remember that some 2000 years ago in Europe, a group of madmen fought

and won against an evil empire in the name of an idea that most thought

not just subversive at that time, but even beyond the thinkable. And

they believed so much in that idea that they accepted to die for it

In

the end, there is more to religion than just fixing a broken economic

system. There is a fundamental reason why people do what they do:

sometimes we call it with the anodyne name of "communication," sometimes

we use the more sophisticated term of

"empathy," but when we really

understand what we are talking about we may not afraid to use the world

"love" which, according to our Medieval ancestors, was

the ultimate

force that moves the universe. And when we deal with Gaia the Goddess,

we may have this feeling of communication, empathy, and love. She may be

defined as a planetary homeostatic system, but she is way more than

that: it is a power of love that has no equals on this planet. But there

are things that mere words cannot express.