This post is an excerpt from the novel that I am writing that should be titled "The Dance Never Ends". The protagonist is an American veteran of the Great War with the plain-vanilla name of Robert Smith who moved to Paris in the 1920s, hoping to follow the flamboyant career of writers such as Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald. There, he becomes obsessed with the story of Mata Hari. He tries hard to forget, to dedicate himself to something more productive, but eventually he engages in an in-depth search.

I remember those days of feverish activity. Reading and taking notes at the National Library that I then brought back home, depositing them on my desk. My old typewriter started looking like a transatlantic liner navigating in a white sea of sheets of paper. And, like the Titanic, it looked like it would sink in that sea and never resurface again. But that was not to happen. I would need that typewriter, sooner or later.

I took time; first days, then weeks. I started with the card on Mata Hari that they had in one of those majestic cabinets, at the library. That told me her birth date, on 7 August 1876, and the date of her death, 15 October 1917. She was 41 when she was shot. The card also said that her real name was Margaretha Geertruida MacLeod (née Zelle) and that she was born in Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. Of course, she was not a Javanese princess; that is, unless you suppose that Javanese princesses can be born in small villages in the Netherlands. She also had married someone named McLeod; not exactly the name of an Oriental prince.

From then on, it was all about news reported in newspapers. I would have needed a couple of research assistants for a thorough search, but that was out of the question considering the state of my finances. So, I started with the 1st of January 1900 – just as a round number - and on I went, one issue after the other of “Le Petit Parisien,” the main paper published in Paris at that time.

For a while, I found no traces of a pretended Oriental dancer named Mata Hari but, in 1905, she appeared as if magically summoned from some otherworldly realm. In the issue of March 13 of Le Petit Parisien, I found a detailed report of her performance in Paris, apparently her first performance ever. It had been at the Musée Guimet, a private museum of Oriental art. Other newspapers published reports of that performance. In all of them, she was referred to as “Lady MacLeod,” although they also mentioned her stage name, Mata Hari. Other papers reported the story a few days later. So, at page 165 of the No. 1 of the 1905 edition of the “Revue francaise de la paix” they said that her dances “hinduistes” or “bramaniques,” and the way she danced was said to be “souple et serpentesque.”

From what I could read, it seems that what she did was not much more than stripping naked at the sound of exotic music. But she seemed to have been hugely successful at that. I found that, later on, she even performed at the “Palace au Trocadero” a place in Paris where anyone who was supposed to be an artist would perform.

Some newspapers had printed pictures of her, surrounded by a group of girls dressed in black, a sort of tunic that left their shoulders free. Mata Hari wore a jeweled costume. A classy woman she was: a tall, hourglass figure, a certain air of distance.

I kept going; she must have continued with her performances. As I moved onward, the news about her became less frequent. That didn't mean she wasn't performing; of course. She might have been somewhere else in Europe or, more likely, there was a certain logic in her having slowed down. After all, she was 29 when she started stripping naked in public. As years passed, it must have become, well, let's say a little awkward for her to keep doing that. And then, the war came, in 1914. The French had different things to worry about than an aging dancer who pretended to be a Javanese princess.

But the interest in Mata Hari picked up again in 1917. In June 1917, all the French newspapers were reporting on her arrest in Paris with the charge of espionage. Actually, they reported that she had been arrested much earlier, in February, but the whole affair had been kept secret. In my notes, I marked that she had been arrested for “espionage, attempted espionage, complicity in espionage, and intelligence with the enemy.” Quite a list, if it was true.

I didn't find much about the trial, it was only reported that it had been a military tribunal judging Mata Hari. According to the press, the sentence that declared her guilty was passed on July 24. She was shot on October 15, 1917. The papers covered the execution the day after, mostly on their first pages. They were not nice to her.

The Petit Parisien wrote that “the spy, Margaretha Gertrude Zelle, who had profited of the hospitality given to her by our country, to betray it for several years.” Le Matin announced the execution of the “Fake Hindu dancer, traitor.” Another daily said that “the salaried spy has paid yesterday her debt to society.” The way most papers presented it, Mata Hari seemed to be a giant cockroach that had been squashed.

Only “L’Heure,” was not so nasty and I copied almost all of their piece in my notes It said that Mata Hari “….died showing a courage never seen before, with a smile on her lips, as when she was triumphant on the scenes”. They said that Mata Hari had refused to be tied at the stake and to be blindfolded. Just before being shot, she had said “merci monsieurs,” (“thank you, gentlemen”) to the soldiers in front of her and she had sent them a kiss. An incredible courage; and that from a woman. Another detail that I found in one of these papers was that one of the members of the squad had fainted before firing. They had to take him away on a stretcher.

I remember that I would shake my head as I was finding these details. You may ask me who am I to judge, sure, but the whole story seemed to me completely fake. You probably know the concept of “kangaroo court” and one thing I can tell you: I was in the trenches during the war and I think that the Germans had no need of Mata Hari or anyone else to know how to kill us. They knew that very well by themselves. Maybe I was wrong, maybe she had been as evil as she was said to be. Maybe she could somehow guide the German artillery, or their planes, or their snipers. But, come on! The whole story made no sense.

Then, I found a curious report describing Mata Hari’s funeral. Her body was placed in a coffin; the coffin was carried to a cemetery, and then lowered into an empty tomb. But it had stayed there just for a few minutes, the time for a priest to say a short service for her. Then it had been pulled up again to be taken to the faculty of medicine “for medical experiments”.

Medical experiments? That could only mean an autopsy on a surgery table. I even noted the names of the professors who had performed those “experiments” on her: monsieurs Branca and Prenant. What idea was that? If they wanted to have fun with dead bodies, in 1917 they had plenty of bodies to enjoy themselves with, fresh from the frontline. Why did they need Mata Hari’s body? Did they need an autopsy to know what she had died of? Did they want to count the bullets in her body? Did they think they could discover something special in her? Maybe they thought she had something inside like an organ of evil, just as we all have a liver, a stomach, guts, and all the rest. Maybe some people really have an organ of evil. Maybe removing it from people, just like an appendix, surgeons could cure the world of evil.

But it rather was this story that seemed to be truly evil. Those professors and their students, those who had dissected Mata Hari’s body, maybe they found it more interesting than usual. Maybe they had fun in stripping her naked. Maybe they posed her on the dissection table. Maybe they were eating sandwiches and telling dirty jokes to each other while they were cutting her to pieces. I could imagine that they could have saved some pieces of her body as if they were relics of some saint of old: a bone, a curl of hair, a whole finger, that kind of things.

One report said that Mata Hari’s head had been embalmed and conserved in the museum of anatomy in Paris. Can you imagine something weirder than this? If I had written that in a novel, you would say that I am sick in my head. But, again, the whole story made no sense. It looked like a bad novel, written by a poor writer who had run out of ideas and tries to keep the reader interested by telling of grisly details about spattered blood.

The final straw came from a book that I had found in one of those bookstalls they had along the Seine river. A book titled “Espionnes à Paris” (“women spies in Paris”) written by someone named Emile Massard, the commander of the Paris garrison during the war. So, this Massard surely knew a lot about Mata Hari and he said he was reporting “the truth” about Mata Hari. The Truth? Who had said “what’s truth?”

Let me give you an example of what Massard thought truth was. He reports that, at the trial, Mata Hari answered to a series of questions about staying at a hotel near the front line, in 1916. And here is how Massard tells the story, reporting how one of the judges interrogated Mata Hari:

When you were at the front line, did you know about the preparations for the offensive of 1916?

I knew that from friends, officers, that something was in preparation. But even if I had wanted, I wouldn’t have been able to inform the Germans, and I didn’t inform them because I couldn’t.

Yet, you were always in contact with Amsterdam through the Dutch legation where they received your letters thinking you were writing to your daughter.

I was writing, I confess, but I wasn’t sending any information.

We have proof of the opposite. We know at least to whom you were writing.

At this point, Massard writes, “At this statement, the dancer paled. She understood that someone had ‘looked’ in the mailbox of the legation, and she didn’t insist.”

Now, I don’t know what you may think of that, but around my place, back home, there used to be a term that describes this kind of things. It is what bulls make from their rear end. I know, it is not proper to write this kind of words in a book, but you understand what I mean.

What was Mr. Massard trying to tell us here? Was he asking us to believe that Mata Hari was completely stupid? And also that the president of the court was stupid? And not only that, that the whole war council was composed of stupid people; actually that everyone else in the world is stupid, including the poor clods who would sort out some of their francs for his book (to be exact, the cover price was 6 francs and 75 centimes). Would Massard want us to believe that the only way for the Germans to discover that a major French offensive was in preparation was to have Mata Hari telling them that? Would she figure that just by looking out of the window of her hotel? Then, of course, what we saw buzzing over our trenches were not German airplanes, just giant mosquitoes painted with the German iron cross on their wings.

And then Massard want us to believe that Mata Hari sent the information by means of a letter traveling by the regular French postal service. And that the letter is addressed to the Dutch legation in Paris, and from there it is supposed to go to Mata Hari’s daughter in Holland, and from there to somebody in Germany, and finally, to arrive to the German headquarters before the offensive starts, actually in time for the Germans to do something about it. Sure, maybe the letter flew by balloon from Amsterdam over the front lines and then miraculously landed right on the desk of General Luddendorf, the commander in chief of the German Army. Won’t you believe in that? Sure.

And didn’t Mata Hari imagine that somebody could open and read her letters? Surely she couldn’t have imagined such a thing, so that she wrote her reports for the Germans fully in clear, although in Dutch. Of course, she must have thought that she was the only person in France who could read Dutch. Come on, even the poor infantrymen of the front line, and I had been one of them, knew that our letters to home were read; all of them. And none of us was so stupid to write in our letters things that would have brought us straight in front of a military court.

So, you see? it was on this basis that they had concluded that Mata Hari “had maybe 50.000 of our children killed,” as Massard wrote. As I said, stuff coming out of a bull’s derrière.

Not convinced yet? Let me give you another example. At page 63 of that yellow book, Massard says that Mata Hari “danced” in prison. He also says that she had told to the prison commander that she needed to take a bath everyday, and that this daily bath had been granted to her. Sure, that wartime military prison really was a high-class hotel. So, why not tell us also about a milk bath, as they say Cleopatra used to have? And would you believe that Massard tells us just that? Yes, he says that Mata Hari had the pretense of asking for a milk bath, and that gives him the excuse for a little show of moral indignation. “Can you believe,” he says, “that this Mata Hari had asked for a milk bath in a moment when there was no milk for our little children”?

Sure, can you believe that?

I could go on, but I guess this is enough. The only thing that I would add is that, in Massard’s book, there were not just lies and obscure claims that Mata Hari had done the most horrible things. Massard lost no opportunity to insult her. Not the least offense was to call her always “Mata”, just as if that was her first name. Now, I may not know Javanese, of course, but it was Massard himself who said at the beginning of his book that “Mata Hari” meant “the Light of Dawn”. No way for him not to understand that calling her just “Mata” was, simply, an insult.

And insults did he pour on her. That she was vain, greedy, rapacious, stupid, haughty and more; besides being, of course, a prostitute. Massard found also the time to criticize her written French. Now, from what I knew, I understood that Mata Hari could speak and write at least four languages: Dutch, German, English, and French. I think she could speak also other languages, probably some Spanish and some Italian. Then, having lived in the Dutch Indies, she must have picked up Javanese, enough at least to take up the nickname of “Light of Dawn”, Mata Hari. And this pompous colonel who, most likely, couldn’t speak anything but French, had the nerve of criticizing her for the mistakes that she made in writing her letters in French.

That’s the kind of thing that drives me crazy. You go some place, you take pains to learn the local language and the locals, instead of praising you for your effort, criticize you for the mistakes you make, for your foreign accent, and for not being able to catch their jokes right away. Yes, that drives me crazy, also because it was what was happening to me all the time in France. . . Sorry, I go mad every time I think about that. But let me not digress.

I had in my hands a book of insults and lies. But it was not just that. There were, there may have been, grains of truth in this onrush of lies and insults. At least, Massard had been present at the execution. When he said that Mata Hari had “behaved well” at the execution, he was describing something he had seen with his very eyes. So, it was true what I had read in some newspapers; that she had refused to be tied at the stake and to be blindfolded. It was true that she had smiled just before being shot; that she had sent a last kiss to those who were surrounding her. That much I could believe; after all, Massard had been present at the executution. And that was something that led even Massard to comment with something that was at least a half praise. It was, he said, a “Grande Dernière”, the last performance of an expert comedian. Not that, according to Massard, it was anything so special, though. He said that the whole set up of a military execution is very formal and very impressive, so that in most cases people “behave well” when they are about to be shot.

I am not so sure about that. If that were the case, why would the prisoner always be blindfolded and tied to the stake? But, after all, what do I know about firing squads and executions? In war, I had been shot at many times, all right, but it had been nothing like people in high uniform lining up to aim their guns at me all together. Just people trying to kill me the best as they could and, thank God, failing at that. Better said, succeeding only in part, considering what had happened to my leg. But let me not digress again.

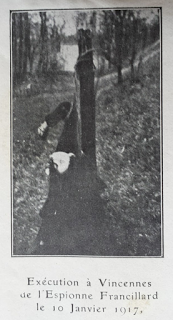

At least one thing that could have been the ultimate insult to Mata Hari was not in Massard’s book. No pictures of the body of the dead Mata Hari. Not that Massard was beyond showing us a picture of a dead woman. He did exactly that with another espionne, a female spy shot at Vincennes a few months before Mata Hari: Marguerite Francillard her name. I won’t go into details of what Massard claimed this Miss Francillard had done, let’s just say that she deserved only a couple of pages of vague accusations. It seems that her mistake had been to be in love with a German man who lived in Switzerland. Then she may or may not have carried letters for him around, but did it matter, really?

Poor Marguerite; they had framed her so well. Think that Massard himself said that she was, in the end, a “good girl.” When she was already tied to the stake, those ugly idiots even convinced her to scream, “I ask to be forgiven by God and by France,” as if she had to submit to a couple of married divinities. Yes, like if Santa Claus had married the Tooth Fairy. Those who had planned the whole thing must have been grinning under their mustaches when they heard her accusing herself in that way. Then, Massard shows us a picture of Marguerite Francillard, dead, hanging from the pole by an arm still bound to it. Poor girl, what a way to end – insulted, killed, and then shown to everybody in death as if she were an old piece of cloth left hanging to dry. So, we can see her after she was, using Massard’s term foudroyée, “hit by lightning”. Yes, in Massard’s book spies are not just shot, they are hit by something like a divine blast; something that they fully deserve as blasphemers of the ultimate deity: France.

These people, they had this idea, this tremendous presumption; these people thought they were Gods to dispense divine punishment. They thought they had a divine right to send lightning from the sky to smite these women. And Mata Hari had the grace and the class of reserving for this gang of louts one of her best performances. Maybe her best ever. But they didn't care about her career, her dances, all the languages she could speak, her Javanese, her French, her German, her Dutch. Everything blasted away, vaporized, gone, foudroyée. And Mata Hari was gone forever, without return.