This post was published for the first time in 1997 on Ugo Bardi's page of the Chimera myth

The archives of the city of Arezzo, in Italy, report the discovery of the "Lion found outside the St. Laurentino Door" in the pages of the "deliberations" from the years 1551 to 1558, starting at page 102. It is said that on 15th November 1553, as people were digging outside the city walls, there was found this bronze statue together with many smaller statues. The archives report how everyone was impressed by the antiquity and the elegance of the "lion" and of the other statues (nempe hoc qui viderunt omne admirati sunt et operis antiquitatem et elegantiam). Only at a later time, about one year afterwards, a note written by a different hand reports that since the snake-shaped tail was missing, nobody had recognized the lion as a Chimaera (serpentis in hoc leone signum erat nullum: non fuit ideo arbitratum esse Chimaerae Bellerophontis simulacrum).

The discovery is also reported by Giorgio Vasari in the second edition (1568) of his Vite dei piu' eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architetti, where he says that Having in our times, and that is in the year 1554, been found a figure in bronze made for the Chimaera of Bellerophon, while digging trenches, ramparts, and walls in Arezzo. In another book, the Ragionamenti, Vasari informs us that in the same year a fragment of the tail was found among the various pieces brought to Florence. In both documents the date is one year later than the one written in the archives of Arezzo, and it seems likely that Vasari had in mind the year when the Chimaera arrived in Florence rather than when it was dug out of the ground in Arezzo. We have also some images of the tailless Chimaera. The one shown here was made by T. Verkruys in 1720 and it gives us some idea of what the statue looked like after the discovery.

There has been some debate in modern times (Ricci, Nuova Antologia 1928) about the possibility that the Chimera of Arezzo may actually have been discovered much earlier than in 1553. According to Ricci, it could have been discovered as early as in 10th century and later re-buried in the place where the "official" discovery was to take place. This hypothesis is based on the observation that Chimeras very similar to the one of Arezzo were painted or sculpted in medieval in 11th century in Italy, especially in some areas of northern Italy, for instance in the cathedrals of Aosta and Merano. Ricci's theory has some interest, but it is based on a very thin chain of reasoning. The fact that creatures which look like classic Chimeras were painted or sculpted in 11th century can be explained simply as meaning that the aspect of the classic Chimera, was never completely lost in medieval times, just as its literary description by Homer, Hesiod and later authors remained well known. In classical times, chimeras were all represented in the same standard way and there is no really compelling reason to assume that medieval chimeras must be derived from a single specific statue, it is even less compelling to assume that this specific statue must have been the Chimaera of Arezzo. Ricci's theory, however, led to the commonly reported legend that when the Aretines unearthed the Chimaera they were overwhelmed by superstitious terror. Needless to say, no such terror is reported by the original sources.

The Chimera and the other small statues discovered in Arezzo were soon transferred to Florence. At the time of the discovery, Arezzo had been under Florentine rule already for about one century and half and when the news of the discovery reached Florence, dukeCosimoI of the Medici family took a keen interest in the statues and ordered them transferred to Florence. The Chimaera was soon exposed in the city hall (Palazzo Vecchio) as a "marvel", and the smaller statues ended in the duke's studiolo, his private collection. Of the arrival of the Chimaera in Florence, there are no records in the city hall, but, as we said, Vasari wrote about it a few years later. Another contemporary report is the one by Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), who is often said to have restored the statue. However, despite the common belief, it is certain that he did not do anything with the tail, which was welded back to the body only in 18th century. It is possible, however, that he restored the left hind leg and the left foreleg. Anyway, here is what he has to say in his 1558 Vita (the life):

Having in these days been found some old things in the county of Arezzo, among which there was a Chimaera, which is that bronze lion which is seen in the rooms near the great hall of the palace (and together with said Chimaera there had been found also a great number of smaller statuettes, also in bronze, which were all covered of earth, or of rust, and of each one of them there were missing either the head, or the hands, or the feet), the Duke took great pleasure in cleaning them by himself, with some goldsmith's tools.

The impression created by the discovery of the Chimera statue in 1553 was considerable and we should not be surprised if the duke of Tuscany himself was interested in it. 16th century was a time of great interest in everything Etruscan. The fashion started perhaps with a Dominican monk, Annio da Viterbo (1432-1502), cabalist and orientalist, who published a book titled Antiquitates where he put together a fantasious theory in which both the Hebrew and Etruscan languages were said to originate from a single source, the "Aramaic" spoken by Noah (of the ark) and his descendants. Annio also started excavating Etruscan tombs, unhearted sarcophagi and inscriptions, tried to decipher the Etruscan language, but he was just the starting point of a wave of interest that was to last basically the whole Renaissance period. There was also a political overtone in this interest, as it helped the growing nationalism of regions such as Tuscany to find a source of cultural identity distinct from the "Roman" one. The statue of the Chimaera, alone, could not have been the origin of all this interest, but it must have helped to stir curiosity, and surely it was an important element of the Etruscan revival.

Over the years, the "political" meaning of the Chimera of Arezzo and of the Etruscans, as a symbol of Tuscan nationalism waned and eventually disappeared. The Chimaera left Palazzo Vecchio in 18th century to be placed in the larger spaces of the "Uffizi" gallery. At that time, the florentine sculptor D. Carradori (or perhaps his master I. Spinazzi) restored the statue again, adding a tail, the one that we can still see today. Then, in 19th century, the Chimaera was again transferred to what is its actual location, the National Archaeological Museum, in Florence. Today, the Chimaera of Arezzo is the pride and possibly the best known piece of the Archeological museum where you can see it just at the entrance, in a room of its own.

Reproductions of the Chimaera of Arezzo.

Reproduction of ancient statues by means of molds taken from the original are not often allowed nowadays since the process may damage the precious original. It seems that no reproductions were made of the Chimera of Arezzo until relatively recent times, in the 1930s, when a considerable revival of everything ancient and classical took place under the influence of the Fascist government. From a mold taken on the original in Florence, two replicas were made and placed in front of the Arezzo train station, where they still stand today. These replicas are of excellent quality although, unfortunately, their placement is less than satisfactory. The Chimaera is a relatively small statue and that it needs some focussed attention to be appreciated. Large spaces and busy intersections, such as the station square in Arezzo, are not exactly what is needed for that. Another replica of the Chimera was placed in 1998 under the arch of the Porta S. Laurentino, in Arezzo to commemorate the discovery. This one is about one third of the original.

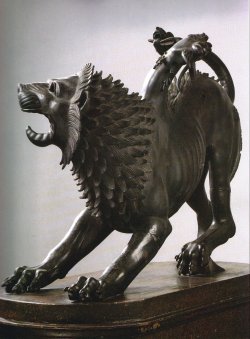

Over the years, more replicas were cast and hence original size copies of the Chimaera are now commercially available (the one in the picture above is shown here courtesy of Galleria Frilli in Florence).

Over the years, the "political" meaning of the Chimera of Arezzo and of the Etruscans, as a symbol of Tuscan nationalism waned and eventually disappeared. The Chimaera left Palazzo Vecchio in 18th century to be placed in the larger spaces of the "Uffizi" gallery. At that time, the florentine sculptor D. Carradori (or perhaps his master I. Spinazzi) restored the statue again, adding a tail, the one that we can still see today. Then, in 19th century, the Chimaera was again transferred to what is its actual location, the National Archaeological Museum, in Florence. Today, the Chimaera of Arezzo is the pride and possibly the best known piece of the Archeological museum where you can see it just at the entrance, in a room of its own.

Reproductions of the Chimaera of Arezzo.

Reproduction of ancient statues by means of molds taken from the original are not often allowed nowadays since the process may damage the precious original. It seems that no reproductions were made of the Chimera of Arezzo until relatively recent times, in the 1930s, when a considerable revival of everything ancient and classical took place under the influence of the Fascist government. From a mold taken on the original in Florence, two replicas were made and placed in front of the Arezzo train station, where they still stand today. These replicas are of excellent quality although, unfortunately, their placement is less than satisfactory. The Chimaera is a relatively small statue and that it needs some focussed attention to be appreciated. Large spaces and busy intersections, such as the station square in Arezzo, are not exactly what is needed for that. Another replica of the Chimera was placed in 1998 under the arch of the Porta S. Laurentino, in Arezzo to commemorate the discovery. This one is about one third of the original.

Over the years, more replicas were cast and hence original size copies of the Chimaera are now commercially available (the one in the picture above is shown here courtesy of Galleria Frilli in Florence).

As obvious, an original size bronze cast of the Chimera, ca. 80 cm tall, is not cheap and so the number of such copies made remains limited. To the author's knowledge, besides Italy, original size replicas of the Chimera exist only in Brazil, Mexico and Japan. There exist also commercial, small size "museum shop" style copies of various origin, most are of poor quality. The one shown here, property of the author, is a nice one as these objects go. It is some 10 cm tall, cast in bronze and well done. Unfortunately, with the best of good will, it does not maintain the exact proportions of the original

As obvious, an original size bronze cast of the Chimera, ca. 80 cm tall, is not cheap and so the number of such copies made remains limited. To the author's knowledge, besides Italy, original size replicas of the Chimera exist only in Brazil, Mexico and Japan. There exist also commercial, small size "museum shop" style copies of various origin, most are of poor quality. The one shown here, property of the author, is a nice one as these objects go. It is some 10 cm tall, cast in bronze and well done. Unfortunately, with the best of good will, it does not maintain the exact proportions of the original

The Chimaera of Arezzo as a work of art.

The Chimaera of Arezzo is neither the only existing representation of the classic myth nor is in any way special, except for its size. It does not differ in any significant way from the many images of Chimeras that we have on dishes, coins, vases, and other manufacts of classic times. In all cases we have the same creature, with the lion, goat, and snake heads lined along the body, all approximately with the same proportions and shape. Even the posture of the beast, with the mouth open, the body arching up, and the legs stiffly stretched forward, is always the same. It seems that the ancient artists who took up the task of painting or sculpting a Chimaera thought that it was their duty to be as faithful as possible to the well known and accepted canons, just as today - for instance - an artist would try to draw Mickey Mouse reproducing as closely as possible the same mouse of previous comic books rather than attempting an original interpretation of the theme of "mouse dressed in human clothes".

Surely, however, the Chimaera of Arezzo is the most beautiful and the most impressive of all the Chimeras we have. You won't find in this sculpture the same degree of perfection and refinement that was typical of later Greek and Roman statuary. In comparison, this Chimaera is rough, even a bit primitive, but this may actually add to its character. Perhaps it is worth reporting here the description given by A. dellaSeta in the 19th century (I monumenti dell'arte classica) where two masterpieces of Etruscan art, the Chimaera and the Capitol wolf, are compared.

The Chimaera of Arezzo is neither the only existing representation of the classic myth nor is in any way special, except for its size. It does not differ in any significant way from the many images of Chimeras that we have on dishes, coins, vases, and other manufacts of classic times. In all cases we have the same creature, with the lion, goat, and snake heads lined along the body, all approximately with the same proportions and shape. Even the posture of the beast, with the mouth open, the body arching up, and the legs stiffly stretched forward, is always the same. It seems that the ancient artists who took up the task of painting or sculpting a Chimaera thought that it was their duty to be as faithful as possible to the well known and accepted canons, just as today - for instance - an artist would try to draw Mickey Mouse reproducing as closely as possible the same mouse of previous comic books rather than attempting an original interpretation of the theme of "mouse dressed in human clothes".

Surely, however, the Chimaera of Arezzo is the most beautiful and the most impressive of all the Chimeras we have. You won't find in this sculpture the same degree of perfection and refinement that was typical of later Greek and Roman statuary. In comparison, this Chimaera is rough, even a bit primitive, but this may actually add to its character. Perhaps it is worth reporting here the description given by A. dellaSeta in the 19th century (I monumenti dell'arte classica) where two masterpieces of Etruscan art, the Chimaera and the Capitol wolf, are compared.

To the snarling posture of the wolf of the Capitol, we can counter the leaping one of the Chimaera of Arezzo [..]. It may not in reality have been coupled with her offender, with Bellerophon menacing her from winged Pegasus, still its ferocious and aggressive nature lets us suppose it. And as for the wolf, it carries in its shape the mark of Etruscan art. The feline body has become even more bony, and larger is the evidence of the muscles, but the massive shape of the wolf is transformed here in a sinuous line. And the accent in the expression culminates here too in the head rich of planes and tormented with folds: the huge aperture of the mouth is framed in the stiff hair of the neck.

Typically, the main preoccupation of art historians has been to place the Chimera statue in the context of Greek and Mediterranean civilization. For instance, here is a comment from M. Mandel Capire l'arte Etrusca, 1989.

The Etruscan origin of this splendid bronze has been the object of long discussions; it has been attributed to a Sicilian workshop, or Peloponnesic, or, in any case, to the work of an immigrant Greek artist. Yet, it differs from the characters of Greek works in some details, such as the position of the ears behind the mane, instead of in front of it.

Modern artists have seen the Chimera in different ways but in most cases they have not been able to go beyond the lines and the shape of the classic Chimera of Arezzo. All attempts to vary its proportions do not seem to be very successful, as seen in this image by Giovanni Caselli for the book "Gods, Men&Monsters" by Michael Gibson. The Chimera is, indeed, an alien object in the world of today and it seems almost impossible to integrate it in modern artwork.

An exception may be the Chimera by the contemporary Italian artist Arturo Martini, one of the very few who attempted to revise or redo the Chimaera of Arezzo image according to modern sensitivity. Martini has transformed the female creature into a male one, complete of the appropriate attributes.

Gone is the goat head and the snake is now just a hint. This Chimaera looks - in many respects - more like a dog than a lion. And yet, the rough mane, the posture, and the expression, do transmit something of the alienness and outlandishness of the Etruscan original. At the same time, it transmits something of the violence and anger of our own times.

The Meaning of the Myth.

The myth of the Chimaera is rather well known, even in our days. As Homer and Hesiod report, the Chimera was an awful, fire-breathing monster who terrorized the land of Lycia. The local tyrant, Iobates, dispatched the hero Bellerophon to get rid of it. Duly, Bellerophon carried out the task flying over the monster on his flying horse Pegasus, showering the creature with arrows or - some say - using his spear to thrust a block of lead into the creature's throat. The hot breath melted the lead, and the beast died suffocated.

The standard story does not - however - tell us much about how the ancient interpreted the myth, and of what the Chimaera of Arezzo in particular was supposed to mean. Something that stirred curiosity at the time of the discovery of the statue was the inscription on the right foreleg. The inscription is reproduced here in a 17th century print of a still tailless Chimaera. The same letters could be read also on the griffin shown in the upper part of the print. Various ways to read the inscription were proposed: Timmsifil, Taninhesel, Tiumquil, and others, and assumed to mean the name of the sculptor, or something more fanciful ("revenge", "goat", etc.). Today there is a general agreement on the interpretation proposed by L.A. Milani in 1912 (Il R. Museo Archeologico di Firenze) that it should be read Tinscvil or Tins'vil that means "offered to the god Tin" in Etruscan. Tin, or Tinia, was the Etruscan supreme God, more or less equivalent to the Roman Jupiter, or to the Greek Zeus. This Chimera was, then, a votive offering. We know that the Etruscans used to place bronze statues at their temples. Two thousand statues were said to be the treasure of the Fanum Voltumnae, the greatest Etruscan temple, that was destroyed and sacked by the Romans in 264 BC.

It is difficult for us to understand what exactly could have been the meaning of this sculpture for the Etruscans. For us, a religious votive offering is hardly meant to be a three-headed monster. In this, we see how our way of thinking has changed in the two millennia and a half that separate us from the people who cast and first admired this statue. The interpretation of the myth has been a pastime of professional and amateur students of antiquities since Roman times when, apparently, the mystery of the three-headed creature had become just as baffling as it is for us now. "Rational" interpretations abound, since the time when Servius Honoratus (4th century AD) thought that the ancient could have been naive enough to mistake an erupting volcano for a fire breathing monster. But Servius - like most of us - had troubles in understanding the immense power of myths, a power that resides in that part of our mind that can still see a shadow of those distant millennia in which our ancestors wandered in a world where the forces of nature played their endless game of sun, wind, and storm. Out of this world and this age, when there was no written record and no painted image, there came some of the most powerful symbols that mankind ever conceived. One was the thunder-beast, a creature that embodied the tremendous power of the storm, a creature bringing destructive lightning and thunder, and at the same time fertilizing rain. This was the origin of the Chimera, a creature which is the origin of all dragons of western mythology, a myth that still fascinates us today.

The myth of the Chimaera is rather well known, even in our days. As Homer and Hesiod report, the Chimera was an awful, fire-breathing monster who terrorized the land of Lycia. The local tyrant, Iobates, dispatched the hero Bellerophon to get rid of it. Duly, Bellerophon carried out the task flying over the monster on his flying horse Pegasus, showering the creature with arrows or - some say - using his spear to thrust a block of lead into the creature's throat. The hot breath melted the lead, and the beast died suffocated.

The standard story does not - however - tell us much about how the ancient interpreted the myth, and of what the Chimaera of Arezzo in particular was supposed to mean. Something that stirred curiosity at the time of the discovery of the statue was the inscription on the right foreleg. The inscription is reproduced here in a 17th century print of a still tailless Chimaera. The same letters could be read also on the griffin shown in the upper part of the print. Various ways to read the inscription were proposed: Timmsifil, Taninhesel, Tiumquil, and others, and assumed to mean the name of the sculptor, or something more fanciful ("revenge", "goat", etc.). Today there is a general agreement on the interpretation proposed by L.A. Milani in 1912 (Il R. Museo Archeologico di Firenze) that it should be read Tinscvil or Tins'vil that means "offered to the god Tin" in Etruscan. Tin, or Tinia, was the Etruscan supreme God, more or less equivalent to the Roman Jupiter, or to the Greek Zeus. This Chimera was, then, a votive offering. We know that the Etruscans used to place bronze statues at their temples. Two thousand statues were said to be the treasure of the Fanum Voltumnae, the greatest Etruscan temple, that was destroyed and sacked by the Romans in 264 BC.

It is difficult for us to understand what exactly could have been the meaning of this sculpture for the Etruscans. For us, a religious votive offering is hardly meant to be a three-headed monster. In this, we see how our way of thinking has changed in the two millennia and a half that separate us from the people who cast and first admired this statue. The interpretation of the myth has been a pastime of professional and amateur students of antiquities since Roman times when, apparently, the mystery of the three-headed creature had become just as baffling as it is for us now. "Rational" interpretations abound, since the time when Servius Honoratus (4th century AD) thought that the ancient could have been naive enough to mistake an erupting volcano for a fire breathing monster. But Servius - like most of us - had troubles in understanding the immense power of myths, a power that resides in that part of our mind that can still see a shadow of those distant millennia in which our ancestors wandered in a world where the forces of nature played their endless game of sun, wind, and storm. Out of this world and this age, when there was no written record and no painted image, there came some of the most powerful symbols that mankind ever conceived. One was the thunder-beast, a creature that embodied the tremendous power of the storm, a creature bringing destructive lightning and thunder, and at the same time fertilizing rain. This was the origin of the Chimera, a creature which is the origin of all dragons of western mythology, a myth that still fascinates us today.

But perhaps there is something more in the Chimera of Arezzo, something that goes a bit beyond the standard iconography of the many painted and sculpted Chimeras that have arrived to us from classical times. In most of these images, the Chimera may be lively and full of movement, or it may be rigid and stiff, but never has the expressive intensity of the Arezzo one. Here the unknown artist seems to have wanted to transmit a message. The fiery, fire breathing monster is shown as a lean, perhaps hungry, creature in a moment of suffering. The body is curled in a posture that reminds that of an angry cat, while the mouth is open as if screaming, with the goat's head is reclining down and drops of blood appear on the neck. In several ways, this Chimera is hardly a monster and it is difficult to see it as an evil creature. Rather, it looks like a fighter, a fighter who has fought well, but who is losing nevertheless. We may perhaps imagine that the artist wanted to show the destiny of his people, the Etruscans, who at the time were being invaded and submitted by the Romans. Or maybe it was to show the destiny of the artist himself, who, as all human beings, was going to lose his battle. In the end, we are all Chimeras.

.